When it comes to automation, Tyler LeBrun gets it.

As president of Luverne-based Backdraft Manufacturing, LeBrun and his team help manufacturers implement automation solutions to create efficiency and become more profitable.

But he also recognizes that automation must confront a roadblock of reality that can constrain it from truly improving production, performance and, ultimately, profitability.

“You can go buy a robot, but you’re not ready for it 99% of the time,” he says.

He advises small- and medium-sized manufacturers looking to add automation to think beyond just plopping a robot somewhere on the production line.

“If you’re looking at spending X amount on a robot, you’re going to need to spend about X amount on the upstream process side to make sure that you’re ready for it,” he says. “We all want to hop in and just put in a robotic cell, but for most cases it doesn’t work that way.”

LeBrun points to a custom fabrication company in South Dakota that approached Backdraft for help taking a 30,000-foot view of its process and figuring out if and how automation could help.

“They said, ‘Can you guys do all the manufacturing engineering work?’” LeBrun recalls. “To start, we’re going to get them fixturing and tooling and figure out how to make their flow lines work.” From there LeBrun describes how his company will assess the current operators, where to scale up, and how to remove and rearrange them to make room for a robot.

In short, it’s about planning. But, if done right, automation can transform a manufacturer. It can modernize your operation, improve productivity and efficiency, solve workforce issues, make the shop floor safer and, if executed thoughtfully, make you more profitable.

The fear that once accompanied automation — that it kills jobs — is all but gone. Most manufacturers understand its power, and any company that is considering incorporating automation into its process and is serious about growth should listen to the ones who have already taken those steps.

“It isn’t going away,” says LeBrun, “and it is the future.”

Whirltronics

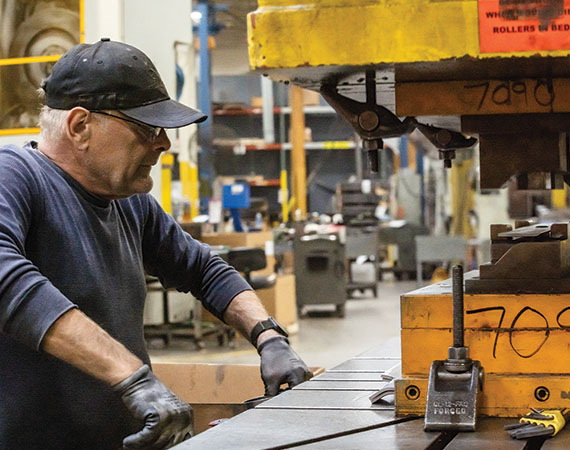

If you’ve pushed a lawn mower in the last few years, there’s a good chance the blade underneath was manufactured by Whirltronics of Buffalo. The company produces about 11 million blades annually for OEMs such as Toro, Honda, John Deere and Ariens.

“We’re shearing, sharpening, heat treating, painting and packaging blades,” says Neil Bengtson, Whirltronics’ director of engineering.

Over the past 10 years, Whirltronics has moved its machine building in-house. The company’s engineering team is designing new production equipment, as well as the automation of existing equipment.

For Whirltronics, automation has been one solution to stubborn workforce issues.

“We have a severe limitation on labor resources,” Bengtson says. “It’s not that we’re replacing people, it’s that we don’t have people. We’ve got more equipment than we can run with our labor pool, and that definitely has accelerated our steps towards automation.”

Bengtson says utilizing automation has made the company leaner. They’ve improved efficiency by identifying parts of their process that can be automated and by using in-house engineers who understand their mission and process.

Ten years ago, Whirltronics was producing about 4 million blades annually. The 11 million figure of today represents about 10% average annual growth. Labor issues, Bengtson says, are part of what’s holding them back from realizing more robust growth. The hope is that adding to their already-substantial automation — nearly every part of their production process includes automation — will consistently keep annual growth at or above 20%.

“Anytime we build something new now we build it either fully automated or automation ready,” Bengtson says. “Our last line that went in is producing at approximately twice the rate of what we did previously, and it uses half the amount of labor to do the same task.”

In addition to requiring less manual labor, Whirltronics set up its automated lines to eliminate the need for human expertise, freeing up skilled employees to work in other areas.

“Rather than having highly skilled people with lots of experience setting it up just right, we rely on the automation through servo-driven adjustments to make sure that even somebody with limited experience is able to set it up correctly,” he says.

While the Whirltronics shop is certainly full of modern tech, it’s also got some old-timers.

“Take a walk through our facility,” Bengtson says. “You can see equipment from back in the ’50s and ’40s even. It’s like taking a walk through time to see the progression from where we started to where we currently are.”

That older equipment isn’t just there to show the passing of time.

“I wish it was,” Bengtson says. “It’s still in use today, it’s still very functional.”

While Whirltronics has deftly infused its process with automation and made use of old and new tech, Bengtson says the company has struggled a bit with allocated resources post-automation. It’s not always as simple as replacing a worker with a robot and then putting that worker someplace else. Often, that replaced worker must still spend some time with that machine. Filling his remaining eight hours, though, can be tricky.

“We try to use those labor resources wisely, and it’s a little bit of a struggle for us,” he says. “Typically, in the past you would put a person on a machine and that was that; there was no management required after they had to make sure that the machine continued to run.”

“But we’ve really had no problem finding other uses for the people. And typically, we’re not displacing people, we’re making their job easier, and then making them more efficient as well,” he adds. “So, we end up getting a return on both the automation and increase production based on the operator having additional time to be able to carry out some tasks. We’ve never let anybody go because of automation. If anything, we’ve added to our engineering and maintenance teams. These automated pieces of equipment require some expertise and ongoing maintenance to keep them running.”

Bengtson says the efficiencies gained by Whirltronics’ substantial investment in automation pay for themselves in about a year.

Dalsin

Imagine a 42,000-square-foot metal fabrication facility with only four on-site employees.

That’s the situation with Dalsin Industries. The company’s main facility is in Bloomington, but they’ve just opened another in Lakeville that is almost completely automated.

“It’s extraordinary,” says Keith Diekmann, Dalsin’s vice president of technical operations. “I don’t know that you’ll find any facilities like that in the metro area. You won’t find that many facilities in the country that are set up similar to that.”

Dalsin’s automation journey began long ago.

The company implemented robust automation systems in the early 2000s that use robotics for material handling and laser-cutting systems.

Automation took certain parts of Dalsin’s process and made it “lights out,” as they say, meaning they could run machines all night long with no one watching and dependably produce high quality parts.

Eventually, Dalsin wanted a more comprehensive automation set up. They didn’t just want cut parts. They wanted finished product.

“We ran that system for a number of years and then when we took our next step forward, as far as laser cutting automation, we looked at it with different eyes,” says Bob Borgerding, vice president of production operations. “At that point in time laser cutting was becoming more of a commodity, and automation became a higher component of throughput. So, prior to automation they would talk about how fast the machine would cut. And we were more interested in throughput.”

Dalsin analyzed its production, wanting to know how it could incorporate the concept of “throughput” into its process. After that analysis, the company switched platforms from Mazak to Mitsubishi.

“That was really the company’s first and most extensive look at what automation could be doing for the company — producing flat blanks in a fully automated way,” Borgerding says. “We’ve deployed similar thinking in punching areas and robotic welding. And then we’ve got the plant down in Lakeville, which really takes all that to a whole new level.”

Borgerding says the Lakeville plant is sort of a peek into manufacturing’s future.

“People talk about the next industrial revolution, industry 4.0, ‘lights out manufacturing,’” he says. “Our new Lakeville facility is really leveraging all those concepts to an extreme. It is kind of the future in a tangible way. It’s a game changer for us.”

Most manufacturers, Borgerding says, will use automation to optimize a particular function such as laser cutting, robotic welding or brake work. Dalsin has taken the next step and linked multiple processes together.

Diekmann says no one has been automated out of a job. The opposite has occurred. They’ve created jobs because of automation, he says. And the increased efficiency has led to more work, more than what is humanly possible.

“There’s no way humans can weld that much, that long, that fast and that repeatable,” Diekmann says. “It’s always been a capacity play. And that’s really what it will continue to be, especially in this labor market.”

When automation replaces a human at Dalsin, that human might move to running the machine.

Diekmann says automation doesn’t cost jobs. “We probably create more new jobs because people need to be able to program robots. The work isn’t the same. It’s different work. But there’s still work, right?” he says. “The more efficient you become, the more attractive your pricing looks, the more work you get — it’s the cycle that every business wants to be in.”

Investment

Getting into automation won’t be cheap. LeBrun says it’s possible to get your feet wet in the automation game for around $100,000. To get a more involved setup, with several work stations set up with robotics, you’re more likely looking at the $200,000-$300,000 range. Most of the projects Backdraft helps people with are in the $300,000 range. And if you’re deploying automation at the level of Dalsin, likely millions of dollars.

This is where small- and medium-sized manufacturers need to make decisions. Are you ready for automation? Does your process lend itself to the kind of help automation can bring? Can you handle the additional work enhanced efficiency is likely to produce?

One thing is certain: Automation isn’t going away.

“Nobody can look into the future, but in talking with different people in the automation realm, a recession may be coming up. But people have been bitten pretty hard already by not being ready for upswings,” LeBrun says.

Manufacturers are growing weary of supply-chain and workforce issues dragging down productivity. LeBrun predicts that many manufacturers who aren’t already making use of automation will begin doing so in the next few years.

And LeBrun isn’t alone. According to Grand View Research, the North American global industrial automation and control systems market size for 2020 was $146.8 billion. By 2028, that number is expected to increase by 8-10% annually.

“I think we do a really good job once we get somebody on board. We start to train them to move them into a more skilled position,” says Dalsin’s president and CEO Tom Schmeling. “But it’s that entry level where we have a lot of turnover still. I think automation is going to continue to be part of our strategy moving forward.”

Says LeBrun: “I don’t see automation going away. What will be interesting to see is how much easier it gets to implement automation. Robots cost $40,000 to make in 1990. They cost $40,000 in 2022. Robots are way cheaper to produce, and the knowledge it takes to program them is getting easier and easier. It’s going to be very interesting to see where that goes in the next 10 years.”

…

Featured story in the Winter 2022 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.