Hung on the wall beneath a gold-hued Fender Stratocaster sits a row of books, with titles ranging from Sound System Engineering and Musical Applications of Microprocessors to Modern Dictionary of Electronics. On one end, a studio monitor — playing At Fillmore East by The Allman Brothers Band — holds the books upright, while the other end is braced by a pair of CD-ripping computer drives. Below them, a workbench lies cluttered with screwdrivers, parts trays, and a wallet that was too thick to sit on.

There’s a bump, a click, and the sound of satisfaction.

One wall away, under a row of Gibson Les Paul guitars, a huddled figure tweaks and twists at his latest design — a top-secret prototype for an out-of-state client. Classic blues licks waft through the room as he wields a soldering iron against threads of molten metal that birth plumes of silver smoke.

We’re in lake country, a short drive from Fergus Falls, and it’s from this riverside shop that Maurice Skogen — friends call him “Mo” — manufactures custom tube amplifiers in the spirit of the 1950s. He estimates he’s built over 900 speaker cabinets in his life, and his work has brought him together with big names. A storyteller by nature, Skogen works away as he recounts that time he refused to sell a prized guitar to Gregg Allman, of Allman Brothers fame, and his brush with guitar legend Les Paul.

“I’ve been in the industry for 50 years,” he says. “I’ve networked. I know all the video guys, I know all the sound guys, I know all the light guys, I know all the studio guys, I know all the bar guys, I know all the churches.”

Skogen doesn’t look like an electrical engineer. His shoulder-length white hair is juxtaposed with smart spectacles. And when you hear him speak — his tone rhythmic, his energy electric — you recognize a child of the ’60s, a man inhabited by the spirit of the blues. His workshop is a collection of HAM radios, classic guitars and flintlock pistols.

“The word’s out there. Everyone knows I’m doing it,” Skogen says. “We’re shooting directly to the touring musician by word-of-mouth through the Nashville studios.”

He shuffles from workbench to workbench, tweaking and tuning, and humming or singing along with the music belting out of his vintage stereo speakers. When the room goes quiet, you can even hear the vinyl spinning on his favorite turntable.

Most of Skogen’s handmade, hand-wired products — under the brand Vintage Voltage — sell in Alabama, Colorado, or through referrals from music studios themselves. And while the business engine churns, Skogen never stops prototyping, always seeking the best switches and potentiometers or a better button.

“It’s just resistors and capacitors. That’s all it is,” he muses.

Growing Up Groovy

Now 67, Skogen discovered his musical passion around the age of 12, in the heart of the 1960s. Compared to today’s artists, music at that time was primal, almost spiritual. It was instinct rather than science.

“When I was a kid, we didn’t have all those guitar pedals (for tone-shaping),” Skogen recalls. “We had to figure it out.”

As his passion grew, he quickly discovered there was no straight road from where he was — the son of a relentless entrepreneur in a small, Midwest town — to the future of stage and fame he would later orbit. Instead, Skogen took a series of retail sales jobs. He sold appliances, VCRs and later personal computers when that technology was still young. From his father he learned adaptability and hard work. The pair spent their days loading refrigerators, stoves, and other household necessities until the mid-1980s, when both father and son suffered disabling accidents.

Skogen’s father was injured falling down an embankment while elk hunting in the Montana mountains, and Skogen traded ski poles for crutches after a slalom accident in 1985. His injuries required 11 skeletal surgeries, and even today he’s recovering from a spinal fusion (his second) last May. Rather than give up, the father-son duo adapted. Two years later Skogen returned to college, making the two-hour commute to earn an engineering degree while raising a family.

In 2000, Skogen took a job with the sound department of Concordia College, and the school’s live performances boomed.

“We started out doing 200 events a year; we ended up doing 650 because that’s how good we were,” he says. “And then the expectations went through the ceiling.”

Skogen was forced to leave Concordia in 2012, however, due to increasing discomfort from his decades-old wounds. But he couldn’t sit still. Retirement in the traditional sense was out of the question, and he wanted to take what he had learned in years of retail and combine it with his passion for music.

“You learn how to read the customer. You learn how to extract information. Now you’ve made a connection,” Skogen says. “People appreciate when you bring them into the conversation. You don’t get that at Walmart.”

Enter Vintage Voltage, the culmination of Skogen’s now 50-plus years in music and engineering. The epiphany hit in January of 2012.

“That’s when I thought, ‘I’m going to be my boss; no more [BS]. I’m going to start doing this.’ That next day, that was my decision.”

Nontraditional Approaches

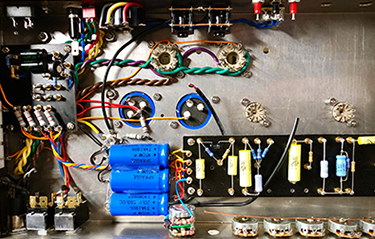

Today, Skogen’s workshop has piles of gadgets and electrical components. He identifies hand-wired, point-to-point electronics that power his tube amplifiers. “These are from the ’40s and ’50s — battleships, submarines, tanks, everything,” he says. “Nobody’s looking at this really anymore except a few people. I’m just learning things that I never learned or finding things that I missed.”

Day in and day out, Skogen dissects classic electronics from decades past in search of the science behind a soulful sound. But the work is never without a challenge. Small things, such as changes in the U.S. energy network, can have consequences that mean his designs need to do more than duplicate vintage audio gear.

“In the ’50s, the wall voltage was 105-110 [volts],” Skogen explains. “Nowadays, its 117-125 — that’s a 20% increase. So, the tube amps, they’re running really hot.”

To tame the sound and protect fragile tubes, Skogen has designed custom power systems that can step down the voltage to safer levels — or leave it cranked to 11, for those who prefer that kind of power. It’s all up to the customer.

His amps are made one at a time, with the chassis produced by local Minnesota manufacturers and the rest done by Skogen’s own guitar-string-calloused fingers. Every unit is tuned to a client’s specifications, and the process can involve months of prototyping. Sometimes, the greatest challenge is cutting through overinflated jargon.

“There are all these terms people use to describe this stuff, and you gotta kind of go, ‘What the hell are they talking about?’” Skogen says with a laugh. “That’s the thing, over time and talking to people — and hearing this and playing that — you know what’s in someone’s head,” he continues, and then pauses. “Kinda.”

Vintage Voltage is a one-man operation, but Skogen’s success is as much from his ability to listen and understand his clients as it is from his decades of experience as a musician and engineer. It’s a combination difficult to duplicate, and he says his only regret was not launching the business sooner.

“I’m thinking now I should have done this 40 years ago, but I didn’t know then what I know now,” he says.

Skogen still plays live shows himself, treating audiences to rhythmic blues and screaming guitar solos. Even if his company looks the same five years from now as it does today, he says he’ll be happy — though he has plans to scale up should the need arise.

Licks and Legacies

Still wondering about that Gregg Allman story? It happened in a roundabout way, but Gregg caught sight of Skogen’s early Gibson Les Paul — signed for Skogen by the legendary guitar maker himself years earlier. As Skogen tells it, Allman wanted the guitar badly, but Skogen wanted to trade.

Skogen had his eyes on a relic of history, a guitar owned by Gregg’s brother, Duane, before his death in 1971. Skogen offered a swap, but no dice. Gregg wouldn’t part with his brother’s memory, and Skogen valued his own axe more than a check with a lot of zeros. So, both guitars stayed put. Skogen keeps his still — though you won’t get to see it without first hearing the Gregg Allman story.

Skogen says it’s that sort of musical legacy that makes it all worth it. For him and his artisan amplifiers, it’s about leaving his mark.

“Some of this stuff appreciates in value over time, and I’m hoping what I build will too.”

…

Featured story in the Winter 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.