When Fosston-area dentist Todd Sandwick came up with a better idea for an orthodontic retainer, no one predicted that his new business would become a cornerstone for innovation and economic development for the city.

Sandwick graduated from the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry and started practicing in his father’s dental office in Bagley in 1993. Soon afterward, he was recruited to join Fosston Family Dental. Sandwick bought the business in 1995 and continues to practice at what is now Smile Designs by Sandwick.

Orthodontic retainers, the final step for most tooth alignment processes, are only effective when patients wear them. But acrylic retainers are thick, often uncomfortable, and tend to produce an annoying “retainer lisp.” They’re also cumbersome to wear while eating, and their porous surface retains food smells and bacteria.

In 2012, after several years of working with young patients whose retainers had inadvertently been tossed into the trash when left on a cafeteria tray or chewed up by the family dog, Sandwick had a better idea.

He designed a cast metal retainer, the Dean Ultra Thin Retainer, named for his father. Today’s metal-printed retainer is about 0.3 millimeters — about twice the thickness of aluminum foil — and is considerably thinner and stronger than traditional acrylic retainers (about 0.7 millimeters). Wearers can eat with the metal retainer in place, and the thin design makes it easier to speak without distortion.

There was no doubt the Dean Ultra Thin was a good idea, but Sandwick needed to find a manufacturer. His wife Melinda encouraged him to patent the device, which he did on the first try, after some good advice to not limit the patent to cast metal retainers.

The first Dean 3s were cast by Johns Dental Laboratories in Terre Haute, Ind., in 2015. But casting dental products takes time and is becoming a lost art. Sandwick needed to find a manufacturer that could 3D print cobalt chromium alloy orthodontic devices.

He had met Bryce Oakes through a mutual friend and admired his ability to think outside the box. Now the company’s COO and co-owner, Oakes, a farm kid from Pembina, N.D., says where he grew up “if you didn’t know what you were doing, you got your neighbors together and figured stuff out.” He brought that collaborative can-do spirit to D3D.

Oakes offered to help Sandwick find a lab to 3D print metal retainers. Sandwick had many connections in the orthodontics field and Oakes had a variety of other connections. Plus, he wasn’t afraid to pick up the phone and cold-call people he didn’t know.

Oakes and Sandwick hit several roadblocks: Some labs said 3D printing wouldn’t work; others said it could, but it was not financially feasible. Most metal 3D printing was happening in high-tech fields like aerospace.

Finally, they connected with a dental lab in Albany, N.Y.

“We sent them sample files to validate the product, which got us very excited,” Oakes says. “Then we made two trips to Albany to learn the process hands-on.”

In 2017, they took the Dean Ultra Thin Retainer to the Northwest Minnesota IDEA Competition, won first place, and earned a spot in the MN Cup, the largest entrepreneur competition in the country. They finished in the top eight there.

In January 2018, Oakes left his insurance career to join D3D and focus full time on developing 3D printed orthodontic appliances. Todd’s wife Melinda had been operating a bakery in a shop attached to the dental office. She also came aboard, and they closed the bakery, converted it into a manufacturing plant, set up their first metal 3D printer, and started printing Dean Ultra Thin Retainers. The date of their first printing — 09-15-18 — is etched on the wall in D3D’s post-finishing room.

The Sandwicks and Oakes applaud the city of Fosston for making things happen as quickly as possible. Todd says about 20 people showed up one day — council members and community leaders — to check out the operation.

They asked, “What do we need to do to keep you here?”

The City, the local Ultima bank, and Minnesota Business Finance worked with the company to keep them in Fosston. The City helped with infrastructure needs for power and utilities as well as financing the adjacent parcel of land for phase two of their expansion. They built a 3,500-square-foot addition onto the plant, brought in two more printers, and started production there in January 2022.

Meanwhile, Sandwick’s team continued to create more metal orthodontic products. Today the original retainer is less than 2% of their business. The company prints various orthodontic appliances for several orthodontic labs throughout the U.S. and Canada.

“I wouldn’t say we’re inventors,” Oakes says. “We’re innovators and adapters. We’re replacing appliances that are analog based — made by technicians, mostly by hand — with 3D-printed appliances.”

Oakes describes one D3D innovation that replaces orthodontic “separators” used to open up spaces between teeth:

“With digital scanning technology, we can design appliances that don’t go interproximal (in between the teeth) or subgingival. Kids are much happier because they don’t have separators that go below the gum line and that could cause discomfort and bleeding.”

Oakes estimates approximately 15% of orthodontists currently use 3D-printed bonded appliances, but within the next three to five years, he believes it will rise to about 90% adoption.

New processes cut the number of ortho appointments needed, opening up the schedule for other dental patients sooner, allowing dentists and orthodontists to see more patients in a day and generating more income.

As patients find the ease of a digital bite scan compared to the cumbersome impression trays full of alginate putty, there’s no going back. Traditional analog appliances take considerably longer to produce and can’t match the precision fit of 3D orthodontic appliances.

Once a patient’s scan is complete, the orthodontic lab sends the prescription and relevant patient information digitally to D3D along with any special instructions. If the order is received by 11:00 a.m. central time, most orders are designed, printed, processed, and shipped by the end of next day’s business.

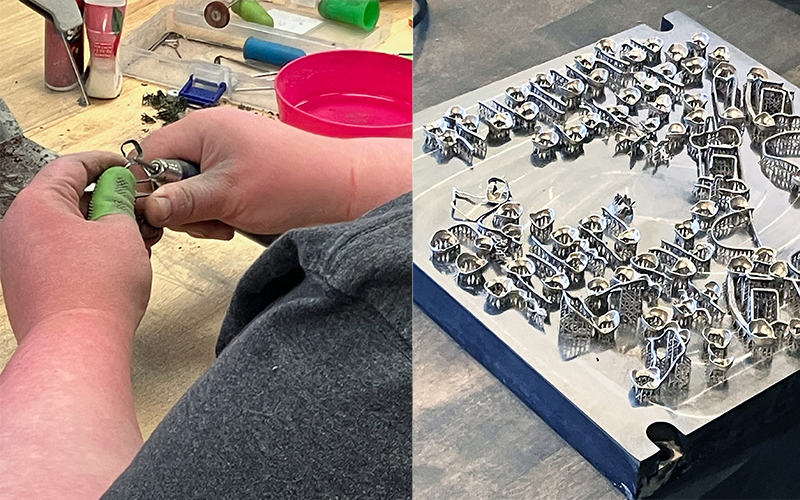

Digital designers manage things on the front end, communicating with the lab, making sure the specifics of the doctor’s prescriptions are clear. As many as 50 appliances can be printed at one time on a “build plate.” After printing, the build plate is removed from the printer and the appliances are heat treated and removed from the plate.

The last step is post-finishing, which involves removing build supports and creating a jewelry-like finish. Each part is checked for fit and accuracy.

Post-finishing is labor intensive. Within the past year, D3D’s post-finishing crew has grown from five to 12 team members. Last summer, D3D experienced a major growth spurt, doing most of the work for over 50 different labs. Only four other labs in the U.S. are printing metal orthodontic devices. This year, Oakes predicts, D3D’s production will more than double.

Oakes attributes the company’s growth and success in their half decade of printing orthodontic appliances to their 27 employees. “We look for new hires who can get along with people and are eager to learn,” he says. “You have to have some aptitude, but a positive, can-do attitude is key.”

The company plans to expand production as more orthodontic clinics and labs adopt the newest and best technologies for their patients. Future areas of growth and efficiency will involve improvements in automation and AI-supplemented CAD design. These advances will allow D3D to produce more products with fewer staff but higher skills and higher pay.

Sandwick says dentists and orthodontists are slowly catching on and becoming more comfortable with hanging up the paradigms they’ve been familiar with for 120 years.

Return to the Summer 2024 issue of Enterprise Minnesota® magazine.