From the beginning, it seemed like a horrible mismatch — think Harlem Globetrotters vs. the Washington Generals.

A team of Lind Electronics package shipping veterans, who had shipped thousands of power supply units and other electronic equipment around the country, were about to compete in a race to see who can package the most parts. Their opponents: Enterprise Minnesota consultants Eric Blaha and Kari Rusing, who together had exactly zero experience packaging anything.

Why, exactly, are they doing this?

“We were struggling to get them to see how minor changes in the way they worked could result in significant improvements,” Blaha says. “So, one day in the middle of class I thought, ‘Well, let’s go try it. We’ll put the masters against the Padawans.’” (The Padawans, of course, being the inexperienced packagers.)

When the race started, the Lind team dropped right into their familiar routine — pre-assembled boxes, printed labels up and down their arms, with warranty cards at the ready. They prepared packages for shipping in batches.

Team Blaha-Rusing prepared nothing. Instead of all that prep, they did it single-flow style, where one person executes one phase of the packaging process — boxing, labeling, etc. — before handing it off to the next phase. Think of it like an assembly line, because that’s exactly how it works.

As expected, the consultants lost…but not by much.

“That was a transformational moment,” says Joe Carlin, general manager at Lind Electronics.

How transformational?

“It changed their whole perspective. After that experiment they were on board with making changes,” Blaha says. “Now they operate everything on a single-piece flow line, and their productivity in distribution has jumped tremendously.”

The point, says Blaha, was that on a manufacturing shop floor — or anywhere else — it’s smart to question how we do things, and whether there’s a better way. The packaging gambit, while technically unsuccessful, proved to be an eye-opener. And it was just one example of leaving money on the table by not examining and improving inefficient processes and long-held habits.

Blaha and Rusing worked with Lind employees and management over several months. They conducted lean assessments and value stream mapping exercises, all to make them more profitable by removing waste and eliminating unnecessary work. And in several instances, those changes produced substantial financial impacts.

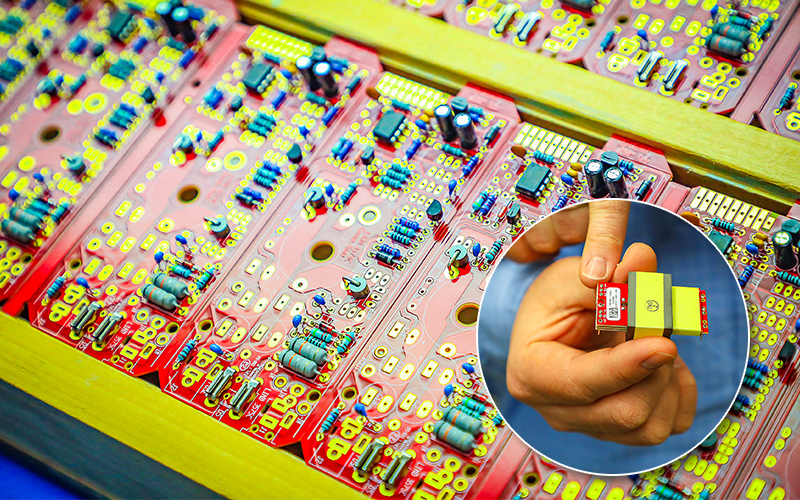

Lind has a reputation of making parts that almost never fail, a value instilled by company founder Leroy Lind, who started the company in the basement of his Minnetonka home. The business’ early struggles disappeared when Lind secured a contract to provide power supplies for Apple computers. That coup would eventually lead to contracts with IBM, Panasonic, and other tech industry giants. But while the industry evolved and Lind evolved with it, one thing never changed: an almost compulsive commitment to quality.

Lind’s quality control process required that parts are double, and sometimes triple, checked, even when the manufacturing process had progressed to a point where it’d be impossible to fix the part. Through value stream mapping and data analysis, Enterprise Minnesota helped Lind put quality in the process rather than inspection, which reduced waste.

“Lind has been known for a really, really high quality product. But they’ve achieved it at their own expense because they over-inspect,” Blaha says. “So they’re spending massive amounts of money to achieve those last couple tenths of a percent.”

Added Carlin, “We were just adding a tremendous amount of waste to that product. We figured out we removed about a half-million dollars for the cost through that exercise.”

This realization led to brainstorming, with employees offering ideas on how to improve that process without sacrificing quality.

The result?

“By partnering with Enterprise Minnesota we recognized enormous capacity gains through workflow design,” Carlin says. “We also realized we were tripping over dollars to save dimes.”

Carlin suspects the company wouldn’t have enjoyed this gain without the guidance of Enterprise Minnesota as a neutral, third-party observer.

He says that production employees might have been skeptical of a request to perform their jobs differently to become more efficient and save time and money. But the way Blaha and Rusing helped employees visualize ways to improve was softer, easier to swallow.

“That neutral party facilitation gave them a voice in the process, gave them a voice in the innovation and the fixing of the workflow design — in a way that we wouldn’t have gotten had we done it internally,” Carlin says.

Carlin says both he and Lind’s operations manager could have executed a value stream mapping session with any department at the company. But, he says, had they done that the ultimate message would have been prescriptive, or like a decree. With Enterprise Minnesota consultants delivering the message, it came sans agenda. They just want to help the company get better, Carlin says.

“Doing it this way gives them the voice,” he says. “They have ownership of those ideas. I think that was a big part of success.”

Return to the Summer 2024 issue of Enterprise Minnesota® magazine.