With the help of more-than-cooperative local partners and the state’s unwavering financial support for its solar module production plant in Mountain Iron, plus a market enhanced by federal government programs, Canada-based Heliene Inc. expects its 2023 solar panel sales to exceed $300 million.

In May 2017, the business took over a 25,000-square-foot facility previously financed for Silicon Energy by the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation with the help of a $3.6 million loan to the city of Mountain Iron. The plant’s production had dwindled to nil, but now the community of fewer than 3,000 residents is home to the nation’s second-largest manufacturer of solar modules.

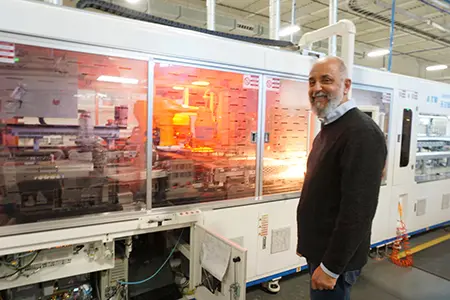

Under Heliene’s leadership, the plant has more than tripled in size. Martin Pochtaruk, Heliene’s co-founder and CEO, says most of the company’s sales will be into the U.S. market. He predicts about 30% of the product will continue to come from the Canadian side of the company, based in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.

Heliene provided laminates to Silicon Energy prior to its closure, but Pochtaruk says the relationship never accounted for more than 10% of the Canadian company’s sales.

“They decided to close in April 2017, and we took over May 1, three weeks later,” Pochtaruk recalls. Heliene wasted little time putting the facility to more productive use, installing a new line that boosted the plant’s annual capacity from 20 megawatts in the original factory to 150 megawatts per year by October of 2018 — more than a seven-fold jump. During the same period, Heliene also went from producing around 50 or 80 modules a day to 1,300.

Since then, a newer production line installed in 2022 has the capacity to crank out more than 3,000 modules a day, Pochtaruk says. “We are at 65 to 70% of that now. We should be better, but we’re not there yet.”

He says that Heliene is working “night and day” to push that percentage upward on its newest $10.5 million line.

Jim Schottmuller, a business development consultant for Enterprise Minnesota, says the recent advances in solar technology are truly stunning. He notes that Heliene went from making 280-watt panels to 460-watt modules that maybe are about 10% larger in terms of surface area. The company has the capability to boost that output to 568 watts per module with another relatively modest increase in size.

The facility and the IRRR’s willingness to help finance production equipment first drew Heliene to Mountain Iron, but by 2020 it became quite clear the business needed more room and might need to move on.

The temptation to relocate was quashed by the late David Tomassoni, a 30-year member of the Minnesota Senate who was a tireless promoter of economic development on the Iron Range. Tomassoni initially recruited Heliene to take over the Silicon Energy facility. When he heard the business might move, Pochtaruk recalls that Tomassoni said, “You’re not going anywhere. However big the building has to be, we’ll get you the money.”

“He was such a champion for bringing jobs to the area. He didn’t need anyone telling him what to do. He was on it,” Pochtaruk says.

Support for the construction of a new $12 million 68,000-square-foot addition to the existing plant quickly emerged: $5.5 million came through a grant from the Department of Energy via the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development; St. Louis County chipped in $1 million; and the IRRR lent $5.5 million to the Mountain Iron Economic Development Authority, which owns the building and leases it to Heliene, using those payments to retire its debt.

“It’s always been an impressive facility, and it gets more impressive with their continued expansion and automation,” says the IRRR’s director of development, Matt Sjoberg. “It’s great to see them growing, and hopefully they continue to do so in our region as the industry and the company continue to evolve.”

While Heliene had not yet made any specific requests for additional assistance as of early April, Sjoberg indicated his door is open, saying: “We would like to help in any way that makes sense to accommodate their continued growth.”

Solar panel technology is advancing so rapidly that the line Heliene installed in 2018 has already been rendered obsolete. The company shut it down in December 2022 and plans to replace it with an entirely new line by this fall at an anticipated cost of about $7 million.

Pochtaruk says the plant’s anticipated production is already sold out for the next two years, even with the new capacity. As Heliene strives to increase output, Pochtaruk says the company also is planning to replace its line in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.

“There are enough customers looking for a U.S.-made product that we certainly can sell out. It’s choosing who you sell to that becomes the issue, because we have to say ‘no’ to a lot of people,” Pochtaruk says.

Heliene sells primarily to clients looking to install fairly large commercial solar arrays, with about 80% of its panels mounted on the ground and 20% on roofs.

Supply chain pains

Heliene has encountered numerous supply chain challenges related to tariffs and the pandemic in recent years. “The only constant is change,” Pochtaruk quips.

The company has traditionally sourced its components from volatile suppliers in Southeast Asia and China, Pochtaruk says, but he expects all Heliene’s components, except the glass and solar cells it requires, will be U.S.-made by this summer.

Heliene’s customers have typically relied on investment tax credits to assist with projects, but Pochtaruk says those incentives were slated to wind down in coming years, creating significant market uncertainty. The recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, however, ensured more generous credits will remain available at least through 2032.

“That is what has cemented the demand, and for a long time,” he says. “So, basically we can continue working with the knowledge that the credits are not going to disappear tomorrow.”

The same legislation also promises investment tax credits for manufacturers, like Heliene, that bring solar power capacity to market.

Pochtaruk says the company is contemplating a serious expansion of its capacities, too. “We need buildings to accommodate two new lines in 2024, and the real change coming up is that we want to start manufacturing the solar cells, which are the main components inside our solar modules.”

It will take at least a two-year build-out to enter the solar cell arena, Pochtaruk says, adding that complex mechanical systems will be needed to move chemicals in liquid and gaseous states, as well as to treat wastewater. “So, a major refurbishment of a building will be required, and it is going to take a major investment,” Pochtaruk says. When asked about the magnitude of the project, he says: “We’re talking hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Given the market opportunity and the federal incentives now available, Pochtaruk says Heliene will need to move swiftly and won’t have time to build a plant from scratch. Where that facility will land remains undetermined, but Heliene hopes to pick a destination by late summer.

Pochtaruk explains that his intent is to vertically integrate and produce solar cells that go directly into Heliene’s own products, not those of competitors. The company aims to break new ground, because there is now no domestic production of these key components, leaving U.S. solar panel manufacturers at the mercy of foreign suppliers.

Staffing up

Heliene operates its Mountain Iron plant with four crews working a combined 22 hours a day and reserving two essential hours for maintenance. “That’s the maximum number of hours we can work in a day, and we work seven days a week,” Pochtaruk says.

Heliene currently employs about 125 people in Mountain Iron and aims to hire an additional 100 workers when it replaces its now-idled 2018 production line this fall.

Filling positions has been a challenge, according to Pochtaruk. “Showing up on time for a shift apparently is not fashionable anymore. We have a large need for people, and we need people who show up on time.”

To cast a bit of a wider recruitment net, Heliene has made itself known as a second-chance employer, willing to hire on formerly incarcerated people.

“We need humans who are ready to come to the job and get paid for an honest day’s work,” Pochtaruk says.

Heliene has a relatively young workforce on its production floor, and Pochtaruk says the company offers its employees a very attractive, clean, climate-controlled environment in a region known for its harsh weather conditions.

Heliene’s production is highly automated, and the company works to keep human contact with the product to a minimum, as organic materials can prove detrimental. Robots also are essential to the operation, as assembly tolerances are as tight as one-tenth of a millimeter, literally about the breadth of a typical human hair.

Finding a foothold

Originally from Argentina, Pochtaruk worked two decades in the steel industry, taking jobs in northern Italy, Texas and then with Algoma Steel in Canada, before forging his way into solar power.

Pochtaruk describes many of his job skills as transferrable but acknowledges encountering a steep learning curve as he moved into the renewable energy sector, where the U.S. has been slow to find its place.

Pochtaruk says the U.S. solar power market is roughly one-fifth the size of China’s. The nation also lags Western European countries in solar power generation.

“A little country like Belgium, plus Holland, plus France, will be as much as the U.S.,” he says.

Pochtaruk expects domestic solar energy deployment to accelerate quickly in the coming years, but the U.S. still has a lot of ground to make up before it begins to catch up to other countries.

“When we started manufacturing back in 2010, there was virtually no solar consumption in the U.S. whatsoever. Even the province of Ontario alone had more solar consumption than the entire U.S. market,” he says.

U.S. solar power generation has been hovering at between 17 to 22 gigawatts, and that’s expected to grow to 30 gigawatts by 2025 and to 50 gigawatts by 2030, if not more, Pochtaruk says.

Vital quality controls

“We used to have one quality assurance person here in Mountain Iron. Now, we’re going to have five, because as the operation grows, the expectation that things are done the right way is more demanding,” Pochtaruk says.

“Our clients also have third-party engineering companies coming in to do audits,” Pochtaruk continues. “We have inspections all the time, and the product we make is guaranteed to work for 25 years. So, the need for it to be absolutely perfect is mandatory.”

Keith Gadacz, a business growth consultant for Enterprise Minnesota, worked with Heliene in December 2021 to train additional staff on internal ISO control management systems.

“They had 12 people across their three facilities, so they could have cross-team improvement to drive their business to a better standard,” Gadacz says. “Their growth means they need to continually add new talent to their audit pool. So, then with that growth, they’ve said: ‘Let’s have people trained to look for improvement.’ And that is one of the key elements of an ISO auditor, being able to see and recommend improvement ideas.”

Particularly in the company’s field and with the rigors of the environment in which their equipment will be tested, Gadacz says there is little room for any production error. “It needs to be planned well, executed well, confirmed well, and audited well. I mean, all those things need to show up for them.”

“We need good leadership to make a plan. We need good leadership to guide and coach. We need good systems to audit against, because of the outputs they need to deliver,” Gadacz continues. “And then of course those leaders bring highly qualified colleagues with them to train them up. So, we have that multi-pronged approach: strong leadership, a strong business and strong people.”

Gadacz says of Joanne Bath, who manages the Mountain Iron plant, and Jenny Wang, head of their quality team, “Those two just ooze leadership.”

He says Heliene is operating in a particularly high-stakes arena for quality control. “Sending parts out that are suspect is going to be tantamount to failure when you’ve got a 25-year warranty. So, we need to do it right the first time.”

The most recent round of internal auditor training was the second time Enterprise Minnesota has worked with Heliene.

“One of the problems that comes up with ISO systems is a failure to improve the systems. If there’s just an ongoing system where people are holding to a certain standard, they can lose the focus on improving. And that’s an important piece of creating an ever-changing, always-improving ISO system to make your company better,” Schottmuller says.

Pochtaruk says the effort to improve internal controls in manufacturing never ends.

“You cannot do it one day a year. You do it every day of the year, because basically what you set up are the processes to ensure that everything is controlled, from the procurement of the materials to the shipping of your finished product,” he says. “If you don’t make that part of your process, you haven’t learned a thing.”