It was four years ago now. Doug Wickstrom had worked for over a decade in manufacturing, most of it spent at a custom machine company that serviced the cheese industry. He supervised projects ranging from four-figure tune-ups to multi-million-dollar expansions and construction. He was versatile, able to take on any role from installation and training to project management — and he soon opened his own company after reaching a comfortable six-figure salary. But he was also a family man and farmer seeking a life that included more time at home, and he was intrigued when he received the phone call from Pine Technical & Community College about a total career transformation.

The college’s president, Joe Mulford, says the school is always looking for innovative ways to expand its offerings. There was a hole in the manufacturing department, and three attempts to plug it had failed. To be competitive, the institution needed an automation program, and they had spotted Wickstrom as their man for the job.

“Automation was somewhat easy,” recalls Mulford on the decision to add an entirely new program to the campus. “You can’t be in manufacturing and not be in automation. It’s like being in technology and not having cyber[security]” — another program added in the past few years.

Reviewing his college’s offerings, Mulford explains that every program exists as a spoke in the school’s many “wheels,” automation within the wheel of manufacturing, and cybersecurity within information technology, for example. By adding one new program, every connected degree path is enriched through new opportunities to cross-train students or offer multiple majors. Automation was a perfect fit.

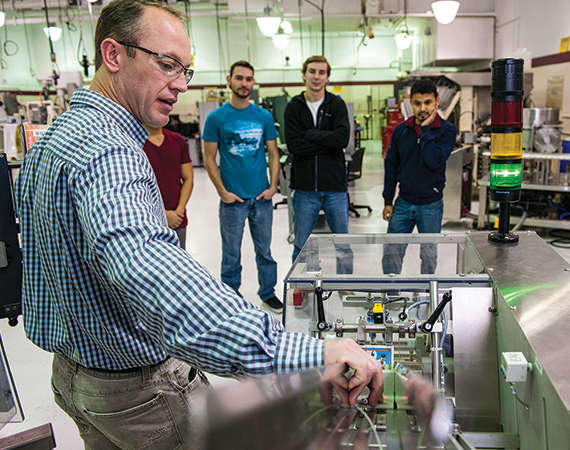

When Wickstrom agreed to create a new program, he feared the college couldn’t support the cost of the specialized manufacturing equipment required — robotic arms, automation software, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), computers and 3D printers. The costs can add up pretty quickly. Luckily, the school had already acquired a portion of the necessary gear before Wickstrom arrived, and he says Mulford and the college’s leadership supported him in everything he needed. They gave him the workspace and a budget; he responded with a custom-built curriculum and by recruiting an advisory board composed of industry experts, hardware vendors and alumni.

A new home

After Wickstrom evaluated the school’s equipment, he decided to build the machinery rather than purchase costly “trainers.” The machinery, he says, gives students an authentic working environment while also saving the college thousands of dollars. Even with vendor discounts, the price tag was hefty. A donation from the Frandsen Foundation, headquartered in nearby North Branch, was met with matching funds to carry the load, and piece-by-piece the program took shape.

Now in operation for three years, Pine Tech’s automation program illustrates how innovative technical colleges are stepping up to develop the next generation of well-qualified industry specialists.

Wickstrom’s students are tasked with constructing their own control panels (he makes a point of not referring to them as “trainers” — these are just as real). Then, rather than plod through a lecture-heavy curriculum, he and his students conceive projects that his apprentices-in-training will be asked to execute to completion. These have included a “torch track,” which navigates an oxyacetylene welding torch from one pre-programmed point to another, a full-scale auto racing simulator with actuators under the seat to mimic the road conditions in the simulation, and even a Chia Pet greenhouse.

Incidentally, the latter is being scaled up to create an automated greenhouse capable of growing a sizable crop of produce (peppers for now) entirely through automated lighting and hydration.

“It’s all started just as you would start anything in industry. There’s no canned curriculum; it’s run as a project,” Wickstrom says. “We focus on problem solving, learning how to learn, learning how to find your answers and being independent.”

It’s that moment after a student hits a wall and then learns to climb over that keeps Wickstrom coming to work every day. The thrill of constant change and new challenges keep him busy rewriting his curriculum, even as he’s sacrificed pay to work as an instructor for nine months of the year.

Mulford says it takes the right person to teach — someone with a desire to mentor and apprentice others. Even with fringe benefits like summers off, he knows many of his manufacturing staff take a pay cut to work for Pine Tech, but there’s something about the sort of person who would sacrifice to improve the lives of others that brings the right candidates.

Keeping the lights on (and plugging in more!)

“It’s about creating value. [Our manufacturing partners] are stepping up and showing they look at this as an investment.”

Dr. Annesa Cheek has served three years as president of St. Cloud Technical & Community College (SCTCC). Speaking on the school’s manufacturing programs — and especially automation for this conversation — she says the college is always looking for new ways to support growing and emerging fields. On the cusp of a roughly $5 million expansion, she’s showing that this mid-Minnesota tech school is making an investment as well.

Like Pine Tech, St. Cloud’s technical college relies on industry partners to guide their curriculum development and introduce new certification programs, pain-point-driven training, and a new wave of employees who are as diverse as the communities they represent. Every program in the college’s manufacturing branch is overseen by an advisory board — totaling more than 300 industry experts and representing some 70 companies and institutions.

“Every academic area in our technical side has an advisory group of business and industry leaders,” Cheek explains. “Our faculty members are working closely with them so they understand what’s going on from a curriculum perspective. They’re looking at our equipment, they’re looking at our labs and our facilities, and they’re making sure that the environment and the experiences that we’re creating here are going to appropriately prepare students for what they’re going to experience in the real world.”

As Dean of Skilled Trades & Industry, Mike Mendez has the college’s advisory boards on speed dial. He says the school encourages their advisors to be critical of its programs to foster improvement. On the materials side, the programs maintain an “ask list,” which they present to board members as a way to procure new training equipment either as a donation or at a reduced cost. Finding the dollars and cents to keep the SCTCC automation program running is about creative problem solving.

“We’re always looking for different ways. Are we leveraging internet resources? Are we working with our advisory boards? There’s no one magic bullet. It’s about being resourceful and seeing who we can reach out to and who can help us along the way,” Mendez says.

And that $5 million expansion? SCTCC received a $2.5 million grant from the Economic Development Administration (EDA) after the St. Cloud Electrolux plant closed in 2019, eliminating 760 jobs. Some of those left jobless turned to SCTCC to retool their resumés, and the EDA grant combined with $2 million matched by the college will be to the benefit of the automation, mechatronics, machining, machine tool and welding programs, according to Lori Kloos, vice president of administration for SCTCC. Kloos says the school’s new “Advanced Manufacturing Lab” will open in fall 2023 and offer as much as double student capacity in the impacted programs while bringing new equipment, cross-training between disciplines and more options for custom-tailored training designed for manufacturers looking to “upskill” existing employees through an accredited program.

Which all begs the question: What kind of person wants to work in automation, anyway?

Work wanted

In the 2020-2021 school year, 60% of the 94 automation students at Hennepin Technical College (HTC) are part-time students. The average age? 29.

As an instructor for HTC’s Automated Robotics Engineering Technology and Manufacturing Engineering Technology departments, Jeff Thorstad resembles the students he teaches. Thorstad nabbed his first degree in social studies and secondary education from St. John’s University. Problem was, that first teaching job never came around, so he took a position as a software analyst instead. He switched paths, selling technical training products to schools and businesses and found himself teaching teachers how to teach with technical and manufacturing equipment. A master’s degree in information security followed, and one day — as he was working on some machinery at the HTC campus — a staff member told him the school had an opening for a teacher.

“Good for you!” Thorstad had said.

But he couldn’t avoid the pull. He applied and took the job, managing another degree in automation and a second master’s in technical education. He still refers to the whole thing as an “accident.”

“Some of the best careers aren’t necessarily a cognitive decision,” he says. “All of the sudden you’re almost literally standing in the right place at the right time and someone asks, ‘Hey, have you ever thought about this?’ and changes your perspective.”

It’s a life path that matches many of the students in HTC’s automation program. Thorstad says many have tried something, gained experience and maturity, and then turn to automation seeking better pay and a better future for their young families. This demographic provides a challenge, however, with many holding down a job and caring for children, so the school has had to adapt. Each program at HTC is offered one day per week, with three start times per day — including nights. Even with so many passing through the school’s door, Thorstad says the market is hungry for more.

“I could literally double the number of students we have in the program and still have more than enough jobs for them. There are a lot of jobs out there for qualified individuals who are willing to look at something other than what they’ve already seen,” he explains.

Thorstad says that manufacturers reach out throughout the school year in hopes of snagging that spring’s graduates, but they’re too late.

“The companies that are really being successful are working with apprenticeship programs, hiring interns, hiring production workers and then sending them to college to upskill. Companies need to work non-traditionally as well in order to find new workers. Simply listing a want ad is not going to get employees anymore.”

So where to begin? About 16 or 17 years old — high school sophomores, juniors, and seniors. Investing in their future early through scholarships and internships can foster company loyalty before a student has entered college, according to Thorstad.

Once they’ve graduated — with an associate degree in automation, mechatronics, or programming in hand — these students enjoy a seller’s market. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median pay for an electro-mechanical technician (a job code that includes automation, robotics, and mechatronics) is $28.75 per hour, or roughly $60,000 per year. By way of comparison, Thorstad explains that the average salary of a student with a bachelor’s degree is around $50,000, and many students require five years to complete their four-year education.

Combatting stigmas, creating solutions

If there’s one statement echoed by every person — students, faculty, and administration — interviewed for this story, it’s that the old stigmas of tech programs as a “lesser education” still cling tight. Wickstrom, at Pine Tech, calls the hiring requirement of a bachelor’s degree nothing more than a “cheap filter” instituted by corporate America. He suggests instead that manufacturers should seek the person best able to do the work.

In St. Cloud, Cheek says her school continues to battle the perception that trade professions are “greasy, grimy” work.

Just as important is a battle against ignorance. Many students and parents, as Mulford explains in his office at Pine Tech, aren’t familiar with automation or mechatronics. Welders and machinists are common titles, but these new fields need time to gain traction, and he says sometimes it’s a matter of slow, steady investments in marketing to overcome oblivious apathy.

And while every college is taking a different route to public education, St. Cloud Tech stands out for their administration of the state’s VEX Robotics program — a competitive K-12 program where students work to design a robot (without blueprints) that solves a certain predefined challenge, such as placing an item in a box. The program is as much about robotics as it is communication and teamwork, explains Aaron Barker, an energy, mechatronics, and instrumentation instructor at SCTCC.

Barker serves as tournament coordinator for VEX Robotics in Minnesota in addition to his teaching responsibilities. He was also named the 2015 Volunteer of the Year at that year’s VEX Robotics World Championship. The program runs competitions every weekend across the state, and St. Cloud plays host to the state championship. Barker says VEX serves as a messenger for automation, robotics, and manufacturing, and the scholarships offered to VEX students steer many to careers in engineering, electronics, and automation.

“We’re out educating the students, we’re educating the parents, and we’re educating the high school instructors to let them know that a two-year degree is a good option and [these jobs] have very good pay,” he says.

Since its inception 11 years ago, the Minnesota VEX Robotics program has grown from 24 teams to more than 500 teams before the coronavirus pandemic.

“We actually have more robotics teams in the state of Minnesota than there are hockey teams,” Barker says.

“That’s saying something,” Cheek agrees.

The VEX Robotics program is not only driving workforce growth for manufacturing and automation. Cheek explains that the program has strong participation from young women (37%) and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) students. Both are important demographics for SCTCC. Cheek says she has often interviewed female and BIPOC students in her college’s manufacturing fields and asked where and how they came to the careers they have. Almost without fail, it’s the referral of a friend or family member who held the influence, and Cheek is looking to let this best-kept secret out of the bag.

“We have to figure out how we create those opportunities and experiences for exposure so that we take advantage of the demographic shifts and leverage that; we want to make sure that employers really do have the talent they need,” she says.

While many colleges were impacted by the pandemic last year, most — including all those interviewed here — have found ways to return to a new normal. Cheek, speaking for her own facility but reflecting the sentiments of her colleagues elsewhere, explains that, “We’re weathering the storm just like everyone else, but we’ve been using this time to position ourselves for what comes next, and we’re excited about that.”

…

Featured story in the Summer 2021 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.