During the first half of the 20th century, large institutions were the de facto standard for the treatment of people with developmental disabilities. In Minnesota, one of those facilities was the Fergus Falls Regional Treatment Center, located near the state’s western border. The sprawling 600,000-square-foot “castle on the hill” once housed 2,000 patients for a diverse range of maladies. Many lived out their lives working and farming on the building’s campus—and then being buried a short distance from the small stone and cement rooms they had slept in at night.

But things changed. Social reform and medical advancements brought about a discontent against the institutional model, which became viewed as little different from a prison. By the middle of the century, there was a push to deinstitutionalize mental health care.

For Fergus Falls, that meant a large population would soon be out of work, but it also meant the community would need to provide homes and aid in other ways for those no longer under the state’s direct care.

Productive Alternatives, Inc. became one of those ways and has been providing social services to Minnesotans since 1959.

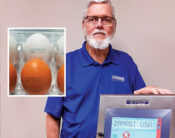

Under the leadership of President Steve Skauge, Productive Alternatives is headquartered in Fergus Falls but operates in seven cities across the state’s beltline. Skauge took over the company 20 years ago, transitioning from his career as a teacher in the Fargo school district (where he watched a similar end to government-run hospitals in North Dakota) to administration in the non-profit care of disabled persons. He views his position as an inheritance of the hard work and ingenuity of the organization’s founders, who saw untapped potential in these now-discarded former patients. With support, the founders envisioned helping fulfill the needs of area businesses through manual manufacturing and providing a productive alternative to a life of private care at home.

“We want people to know that everybody has some capacity to work,” Skauge says.

It took no small amount of grant applications, local fundraising, and even state legislation to finally found a non-profit organization with a name that fit its purpose and that gave life to what was previously only a philosophical position.

Productive Alternatives

Productive Alternatives began as a “sheltered workplace.” Area businesses would contact the company with their basic manufacturing and assembly needs, and Productive Alternatives would hire out their equipment and teams of employee-clients. The operation provided a product, and it also offered those involved a sense of self-worth. But there was a problem.

The company had the staffing, quality control, warehouse, and equipment, but it needed a product. The jobs would come, but once they were done, there was a gap to fill. “It was really difficult to have a steady flow of work,” Skauge explains. And tensions wound up as the labor force went without work.

Rather than wait for work to come to them, the company’s founders saw a niche for goods designed and manufactured in-house. And it worked.

“Filling in the blanks with our own products gave us that almost-never-ending flow of work—and boy was that huge,” Skauge says.

When the community’s needs were high, Productive Alternatives churned out orders. When work dried up, the company produced and stockpiled inventory of its own. Its reputation for reliability and a flexible approach to sub-contracting attracted others. Soon, the company became a beacon for entrepreneurs—home inventors who had an idea but not the infrastructure to manufacture it. Skauge describes the development as a “real incubator for the region.”

As Productive Alternatives grew, its model for supporting a workforce with disabilities shifted. The term “sheltered workplace” represented an ineffective approach that isolated a percentage of the community. And while it was easy enough to see that the company needed to leverage its connections differently, it also meant a radical restructuring to how it obtained funding and operated. But despite facing the most significant challenge since the company’s founding, Skauge and his staff of career coaches, support professionals, and care providers were up to it.

Fiscal Implications

Productive Alternatives was, and still is, a holder of a federal 14(c) certificate. Part of the Fair Labor Standards Act, this certificate allows for the sub-minimum wage employment of persons with disabilities. Because the majority of the company’s revenue was limited to federal and state grants based on the number of clients served, the sub-minimum wage was advantageous. From a manufacturing standpoint, however, the implications on efficiency were backward. Where most companies work to streamline and automate their production lines with only the necessary staffing, Productive Alternatives had the advantage of providing as many jobs as possible. It wasn’t about margins or demand; it was about the number of people helped. And the more people helped, the more funding.

But if the company’s mission was indeed the betterment of lives, a sheltered workplace only improved on the institutional model. It couldn’t match the social advantages and higher wages out in the community. Productive Alternatives wanted its clients to become a genuine part of society, not isolated from it. So, the company built bridges with employers. Job coaches worked to identify positions with high turn over that are difficult to fill and brought in their hard-working clients to fill them.

It’s taken some time, but in the five years since Productive Alternatives transitioned to community-based jobs, it has been a success.

The second-chance employment division is a bit of a misnomer, Skauge explains, as the company provides third, fourth, fifth, and sixth chances, too. By working with the “unemployable”—people with chemical dependency history, mental health issues, and even felony convictions—Productive Alternatives not only produces products, it also offers a service in line with its mission.

“The vast majority of people want to work and need to work, but they have legitimate barriers that are preventing them from getting a job and keeping that job,” Skauge says.

He acknowledges extra steps are sometimes necessary to employ this population, but he doesn’t shy away from it.

“That’s the challenge, but it’s also the fun part,” he remarks.

You’ve likely seen Productive Alternatives’ hand-made products yourself in retailers across the country. For years, the company offered an assortment of ice fishing products, such as the Rattle Reel or the Big Dipper slush and ice scoop, sold at Scheels All Sports, Fleet Farm, and Cabela’s. Its Stratus Rain Gauge is the official rain gauge of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service.

Pandemic

At its zenith earlier this year, Productive Alternatives was a $16 million organization with over 300 employees and more than 1,000 clients served. The company operated public transit systems in five cities and provided day training services for vulnerable adults, chemical dependency and crisis intervention, job coaching, sub-contracting, manufacturing, and employment. By early April, however, the company was a ghost town.

Like Skauge, Productive Alternatives Director of Operations Mike Burke has decades of experience operating non-profit care services. Until last September, Burke was the executive director of the Alexandria Opportunity Center. After the organization merged with Skauge’s, Burke assumed his new role in operations.

“I thought I knew the business,” Burke says. “This is an all-new thing for everyone.”

Burke oversees three Productive Alternatives sites—Fergus Falls, Perham, and Alexandria—and all of the Fergus Falls manufacturing. With his role in operations, Burke has worked to increase profitability and efficiency in the company, which until five years ago weren’t a concern.

“We’ve gone through a lot of transition in the last few years, and this is our shot at making it work,” Burke says. “It’s not your traditional production situation. It’s unique in the fact that we’re a non-profit that runs a business and needs to make money.” But he’s proud of their second-chance staff and their end products.

“The quality’s really good,” he says.

When Gov. Walz handed down the shelter-in-place order on March 28, Productive Alternatives’ clients did precisely that.

“Our revenue just stopped,” Burke says. “We’ve never had a downturn that’s so immediate and so deep.”

Because Productive Alternatives receives approximately 75 percent of its revenue through government funding that is based on the number of clients served per day, that money dried up overnight.

“When they don’t show up to work, we can’t bill,” Skauge explains. “We had to shut down all the way to the very core elements of what we do.”

That meant mass layoffs. A staff of more than 300 became 15. Only necessary services, such as the public transit operations, remained open.

Tina Soland worked in the Productive Alternatives sign shop when the coronavirus struck. She remembers the meeting at which the company announced the layoffs and the fearful words like “if” and “when” that dominated the discussion of the company’s future. As a veteran employee of the company for 20 years, she was one of the few who still had a job.

“I had to get in my car and drive around town for 25 minutes,” she recounts. She didn’t know whether she should cry for everyone they had lost or be thankful she still had work. She remembers thinking, “This is really happening. Everyone’s getting laid off, and there are just a few people left.” In the weeks that followed, as she assumed a supervisory role in the sign shop, she says the building felt empty. Without a demand for the company’s public transit, only some of the drivers would come to help with production.

Red Tape

The legislature determines funding levels for Productive Alternatives and the roughly 100 other care providers like them across the state. That funding determines pay raises, benefit increases, and growth. Skauge says it’s never been enough, and the company has known more cuts than growth. But he is quick to point out the benefits the dollars provide: employing the unemployed and generating income tax and sales tax while providing life skills and satisfaction without burdening Medicare services.

“You’re getting a pretty doggone good return from that tax dollar when we put people to work,” he quips.

The legislature failed to enact a bill that would have subsidized ongoing costs for mortgages, vehicle loans, utility bills, and fixed costs that persisted when the organization shut down. Although the bill’s authors intended the legislation to cover necessary expenses, Burke explains that it became a bail-out for those who otherwise would never re-open. Organizations like Productive Alternatives, which were managing to stay afloat so far, were left without aid.

For 24 years, Rep. Bud Nornes has served in the Minnesota House to represent District 8A, including Fergus Falls and the area surrounding Productive Alternatives’ headquarters. He says he wishes he had an answer for what’s happened to prevent the DHS money from being released.

Nornes says he has contacted the governor’s office, as has the mayor of Fergus Falls, but there’s been little movement.

“Productive Alternatives and programs like it were just overlooked, and I think that’s a travesty,” he says. “It seems very unnecessary to have it idled right now.”

Skauge and Burke say they’re used to working with limited budgets, even if the current circumstances are extreme. In the weeks following the shelter-in-place order, a portion of the company’s production staff have returned to work, fulfilling in-house and sub-contracting orders. The support staff is returning as well, but more slowly—their salaries will only return as clients begin venturing out once more.

“We’re struggling because we don’t have enough money to support our mission,” Burke observes.

“Something’s got to give here pretty soon, or we’re going to have a lot less of a mission. When the state government and the federal government decide that they’ve overspent themselves, there will be cuts, and we tend to be an easy place to cut from.”

Nornes, meanwhile, acknowledges that the state will be tightening its belt. He agrees that funding has never been adequate in the first place and that organizations like Productive Alternatives too often fly under the radar despite their importance.

As to the future, Skauge acknowledges that it may take time for Productive Alternatives to return to the $16 million operation it was before the coronavirus outbreak. Still, he has no doubt the company will survive. Its mission is too important not to, and the company’s clients will need support just as before.

“We’ll survive it in a business sense,” he says, “but we will not look the same.”

…

Featured story in the Summer 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.