As today’s tight labor market has intensified the drive for manufacturers to automate their operations, a Hibbing startup views that fast-evolving manufacturing landscape as a big market opportunity.

Jason Wobbema grew up in Eveleth but moved away to pursue a career in robotics and automation, working 23 years in the field for the likes of Andersen Windows, 3M, and Foxconn. He also helped a German company sell systems designed to keep production workers out of harm’s way.

In 2017, Wobbema returned home to the Iron Range and flew back and forth to work for years. But then, the pandemic struck, and Wobbema’s travels ceased. He rediscovered the pleasures of putting down roots and decided to launch his own local business: Advanced Machine Guarding Solutions (AMGS).

As the pandemic wore on, Wobbema set to work.

“I couldn’t travel anymore,” he recalls. “So, my nights and my weekends turned into product development. And then, I started designing all the equipment to build the product.”

Wobbema was convinced he could deliver a better product than the market offered that assembled easily without loose fasteners, could be custom-fit to the needs of his customers, wired with all the necessary safety features, and that would beat out foreign suppliers by offering a superior domestic option.

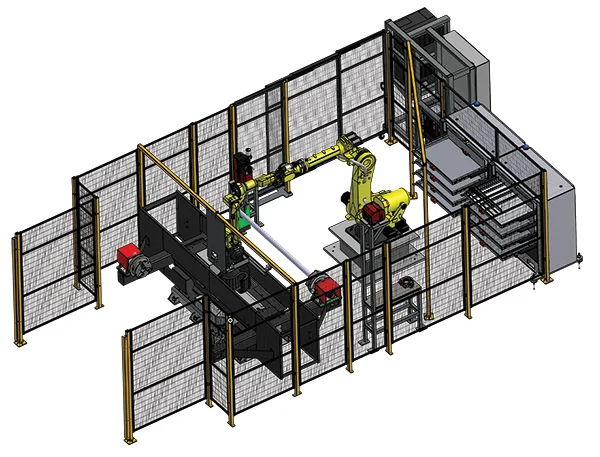

AMGS specializes in safety enclosures and other protective equipment, such as light curtains that automatically shut down machines when a worker breaks an established safety plane.

“We modify our product to be almost like a kit. We supply not only the hard-guarding but also all the electronic safeties to go along with it,” Wobbema says.

Wobbema had helped another European startup in the same arena quickly grow its sales from near-zero to $3.5 million and was eager to beat that former employer at its own game.

Having worked as a robotics integrator for years, Wobbema also was well aware of the shortcomings of products already on the market.

“I continued to buy and use our competitors’ products and never was very satisfied. So, I just thought I could do better,” he says.

Wobbema adds that when it came to installing interlock systems, light curtains or customizing a system with other automatic safety shutoffs to meet a client’s needs, these manufacturers offered virtually no support. “It was always on the customer.”

“What we do differently than our competitors is we make it easy for them to put whatever electronic safeties they want on our system. So, we do the up-front design work,” he says. “We’ll do full turn-key solutions when it comes to safety.”

With some help from Iron Range Resources & Rehabilitation and the Entrepreneur Fund, Wobbema says he launched his pilot manufacturing plant in a 10,000-square-foot space owned by the city of Hibbing.

Wobbema says he kept his expenses to a minimum by building his production equipment from scratch at a fraction of the normal cost. Wobbema figures he sunk about $450,000 into constructing equipment, including a robotic welder and a spot-welding machine, that would have cost more than $2 million to buy off the shelf.

That conservative approach can serve a startup well, according to Jim Schottmuller, a business development consultant with Enterprise Minnesota. “Every dollar counts. Every single dollar you save is a dollar you can spend on something else,” he says.

“The old adage is that about 50% of new businesses fail within five years, and the number one reason is undercapitalization. Historically, that’s been the hard part,” Schottmuller says.

While the pandemic gave Wobbema the breathing room he needed to launch his business, he says it also hindered it in other ways.

“There was a huge buying spree, and we couldn’t get parts, couldn’t get materials, couldn’t get anything. There was so much pent-up demand,” he recalls.

Despite delays, by August 2021, AMGS was ready to begin production. But the complications continued.

“Customers wouldn’t let us in the door to sell because of COVID. It really took another six months for that to even start to open up,” Wobbema says.

For all practical purposes, Wobbema considers 2022 his first real year of business, and AMGS rang up about $500,000 in sales.

In 2023, Wobbema hopes to push sales to around $2 million.

Longer term, Wobbema expects more dramatic growth as he gains client confidence and share in a growing market.

“This company, within five to seven years, can absolutely be a $7 million to $10 million operation, employing anywhere from 25 to 50 people,” he says.

Many of AMGS’s clients fully recognize the need for safety precautions to protect workers from the dangers of automation, but others are less informed.

“We have two different types of customers. We have the guys who integrate the robots, and for the most part they get the safety. They do this stuff every day. They know what they have to do to try to make it all safe. And then, we sell to the end user, who’s the manufacturing company that might be building its own automation or might have some older equipment. We help them figure out how to make that safe and understand what the regulations require you to do,” he says.

“There’s a misconception in the world of safety that there’s some sort of grandfather-clause exception,” Wobbema says. “Some manufacturers think: ‘This machine is 50 or 70 years old, and it is what it is.’ But it doesn’t matter. You have to keep up with the latest technology and safety. It doesn’t matter if you have a one-year-old or a 100-year-old machine.”

AMGS offers manufacturers valuable expertise in the safety field, says Betsy Olivanti, community development director for the city of Hibbing.

“Automation is the wave of the future for manufacturing,” she says. “And that’s truly being driven by our workforce issues. So, in my opinion, AMGS is really on the cusp of being able to integrate automation into their facilities, along with that service and essential support around guarding those operations,” Olivanti says.

“If Jason can get his capacity to where it needs to be to service that mid-cap market, I think he’s just going to be off and running,” she says.

“The shortage of employees is forcing companies to implement automation where they can, and that will only drive demand for his product,” Schottmuller says. “I think this is not a solution for a short-term problem. This is a solution for a long-term problem.”

Schottmuller stresses businesses would be well served to heed Wobbema’s advice in regard to improving safety.

“One way or another, they’re going to learn how important safety is around their machines. And it’s better to learn that from somebody telling you it’s important than it is to learn it because someone gets injured,” Schottmuller warns.

Wobbema says, “There are three reasons a business owner invests in safety: Number one is if your insurance is going to drop you because the insurance adjuster walked through the plant and saw many problems; second is because OSHA paid a spot visit and decided to fine you $50,000 because you haven’t been keeping up with safety; or third it’s an injury or a death.”

That final scenario is likely to be the most expensive.

“Loss of life or loss of limb will usually cost a company more than $1 million,” Wobbema says, and he takes his own advice to heart.

“Like I tell my folks, that robot is absolutely replaceable, $50,000, no problem. Your life is not. That thing could melt in its place, do not go around it. Make sure you safely lock out the machine before we even go in there,” he says.

“Machines are replaceable.”

AMGS is competing in an arena currently dominated by foreign producers of guarding systems. Wobbema estimates 80% of the market is controlled by Europe, India, and China.

He somewhat sheepishly admits to being part of the problem, having helped a German company gain market share before striking out on his own to become a direct competitor.

Wobbema says many foreign suppliers enjoy the benefits of greater automation in their production and lower steel prices, as they can buy directly from a mill instead of buying through a distributor, as he must.

“We’re at a disadvantage using U.S. steel, but we feel it’s the right thing to do because we’re on the back door of the Iron Range. We want to support their business and continue to grow our business,” he says.

Wobbema says some manufacturers are drawn to the idea of buying an American product, too.

“Sometimes, we seem to lose track of where our dollars go. And I tell our customers: Your dollars coming to us won’t really leave the region. And our region needs those dollars for more economic development.”

He acknowledges cost often remains the key determinant, however.

“But in today’s market, with their shipping costs, we can compete,” Wobbema says, pointing to the continued high cost of moving shipping containers overseas.

Schottmuller says AMGS should enjoy another advantage serving the North American market as a domestic producer, because it likely will offer shorter lead times.

With the start of 2023, AMGS plans to open a webstore, and Wobbema says the company’s user-friendly online presence is likely to play a key role in its future growth, with many potential customers cruising the Internet in search of safety solutions.

Wobbema says his company is quickly distinguishing itself as a provider of tailored solutions.

“Every one of these projects has something unique about it, whether that’s cutting a hole for a conveyor or whatever. It’s our ability to customize it for our customers, to withstand North American safety rules, and really provide a product that meets those standards. That’s what most foreign companies don’t do. They simply sell panels and posts. They don’t do anything else,” he says.

“We are much more of a designed solution. So, I’m designing projects for customers. We’re modifying our standard stuff to fit what they need. The other advantage is that we’ll incorporate all of the electronic safety technology,” Wobbema says. “When you buy a steel guard from us, there’s a whole other level of safety equipment that needs to get mounted to it. And we’ll help or do that for you.”

While AMGS stands ready to help customers with risk assessments and design, it does not directly install its systems, although it can connect clients with contractors who will offer that service.

However, Wobbema says most manufacturers find it simple enough to handle their own installation in-house.

“This product is easy to deploy. You don’t need an engineering degree,” he says. “It’s really kind of a turn-key system.”

AMGS employs four people at present, and Wobbema says none of his hires has a college degree. He has personally trained staff up.

“We look for people who want to work and want to learn. We actually pay on the high end compared to other local businesses, because we want a $20-an-hour person to know how to run this equipment, and that skill is really something we can teach internally, which is something that’s hard for other manufacturers because they don’t have a ‘me’ working there.”

Wobbema says AMGS offers staff an opportunity to learn new skills and grow professionally.

“The old way of manufacturing 20 years ago was you hired people to stand in front of a machine, and you went from left to right. You were making widgets, and you were the robot. Nobody wants that job anymore,” he says. “So, now we need people to run two or three machines and let the robots do the work. And their job is really to maintain the equipment and the process.”

Schottmuller praises Wobbema’s efforts to train from within.

“I think the approach to pull young, unskilled folks out of high school and get them involved in manufacturing is the only successful road forward,” Schottmuller says. “If you wait for someone to get through high school and into or through college, I think their paths are probably determined. Many living in places like the Iron Range have already decided that their ability to succeed means leaving town.”

“If you don’t get them engaged before they make that determination, I think it’s tough to change the trajectory,” Schottmuller adds.

Wobbema acknowledges his struggle to scale up production already has cost him precious opportunities to take larger orders.

“We’ve had the demand. We just didn’t have the equipment to meet that demand. And we’re passing on orders,” he says.

Another challenge, according to Wobbema, is that large companies and big system integrators ask: Are they going to survive? “When somebody inquires: ‘Who are your investors?’ And I say it’s just me, they’re not impressed,” he says.

“They’re expecting to see more venture capital to be involved. They’re expecting we’d be getting $10 million in seed money here and $15 million over there. That’s just not how it is,” Wobbema says.

“That’s always the challenge of the startup, is to kind of gauge your resources and scale your capacity to the demand,” Olivanti says.

“The Range doesn’t have the pool of equity that you’d find in Red Wing, St. Cloud or Albert Lea or some of those types of places,” she says. “They all say we’d love to invest, but we’d need you to move down here.”

“The IRRR provides grants around real estate but doesn’t put an equity injection into equipment or the other kinds of things for an entrepreneur to get started. We just don’t have that as part of our capital stack up here for entrepreneurial ventures,” Olivanti says.

Schottmuller says AMGS may be able to leverage the help of a large customer, as investors will look more favorably on a company with a demonstrably strong order book, necessitating imminent growth.

“When you stop selling, that’s when people stop buying,” he says. “Trying to get that momentum back is no fun. I hate it when people have to stop selling or say no to an order,” Schottmuller says.

At the same time, he continues, “If you say ‘yes,’ and you can’t deliver, you will never get another opportunity. It’s a risk either way.”

Wobbema agrees: “We can’t keep turning down these bigger orders and bigger contracts, because they’re not going to come back to us. We’re still working on that.”

Olivanti says she’s not done trying to help.

“I don’t care if it’s angel investors or venture capital investors or whatever, we just need to have some models to provide equity injections for manufacturing entrepreneurs up here,” she says.

For all Wobbema’s savvy, Schottmuller says he’s also smart enough to recognize what he doesn’t know.

“He has a lot of years of experience under his belt. He also is smart enough to know that it’s still important to get opinions from other folks and to rely on them to help where you’re not the expert or where you could use some additional ideas,” Schottmuller says. “He really is open to that.”

“Jason’s participation in Enterprise Minnesota’s Northeast Minnesota Peer Council has exposed him to other business leaders in the area who can help ensure he doesn’t make some of the mistakes he might otherwise make on his own,” he says.

For his part, Wobbema acknowledges coming around to accepting guidance.

“I was a little bit hesitant at first, because I wasn’t sure I understood the value proposition of Enterprise Minnesota. But it helped us connect with local manufacturers and understand their struggles, too.”

And hearing from others has been useful, he says.

“Let’s admit it. My background is in robotics and automation. There’s probably a lot I have to learn about running a business. If someone could bring some of that talent to the table, we would absolutely love it.”