Jashan Eison was 13 years old when his father was murdered.

With Eison and his two brothers to care for, his mother played the role of both parents.

“I always think about the sacrifices she made,” says Eison, CEO of H&B Elevators in Minneapolis. “My mother had little to nothing. But [with] that little to nothing, she gave everything.”

Growing up in Milwaukee, money was tight. Nothing came easily. Even meals couldn’t be taken for granted. When there wasn’t enough, the kids ate first.

By high school graduation, Eison knew he wanted to study construction. He chose the University of Wisconsin-Stout, and once again his mother offered all she could.

“She gave me the keys to her only car so I could get to college—and she took the bus,” Eison says. “Thinking about it fuels me every day.” He pauses once more. “I still don’t know how she did it. She can have anything she ever wants; that’s how I’ll put that.”

Life picked a fight with the wrong family, and while it may not have been fair, the loss and sacrifices made Eison stronger. His experiences prepared him to adapt, and his journey led him to become one of North Minneapolis’s noteworthy entrepreneurs. The Minneapolis-St. Paul Business Journal named Eison in its prestigious 40 Under 40 list in 2017 and awarded him with the Diversity in Business Award in 2014. In 2016, the Metropolitan Economic Development Association (MEDA) named him Entrepreneur of the Year.

“They bought a company, moved it into an area that has needed the kinds of jobs and wages they provide, and cleaned up a building that looked like it should have been torn down.”

His company’s clients have included Facebook, Google and The Walt Disney Company. Projects by H&B Elevators are featured at U.S. Bank Stadium, Yankee Stadium and the 163-story skyscraper Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, to name a few.

“You learn how to tactfully use those survival skills—and sales skills, and people skills and hustle skills—to do what you can in a positive way,” Eison says. “Here I am, a kid from Milwaukee, sitting at the head of a multi-million-dollar organization—you just don’t see it.”

It all began with a gamble.

Creating an opportunity

A business called Hauenstein & Burmeister was founded during the 1920s as a south Minneapolis weather stripping company. By the Great Depression, the company focused on supporting public facilities, becoming one of the first distributors and installers of noise-dampening acoustic ceiling products. By World War II, H&B was crafting wooden ammunition boxes and airplane hangar doors to support the war effort.

Hangar doors led, in time, to elevators, and the company changed hands regularly. New ownerships expanded into construction, bleachers, and low-voltage equipment. When Jashan Eison returned to the midwest in 2005, H&B (under the ownership of the billion-dollar construction firm, Kraus-Anderson) was known for elevator cabs, entrances, and doors.

Eison came on in 2007 as a project manager and dabbled in sales. He went back to school, graduating with a master’s degree in marketing from Marylhurst University—and what he labels as a “false sense of understanding.” Kraus-Anderson had acquired the business believing it would pair well with its primary interest, but the elevator division didn’t fit a company without an elevator or manufacturing background. With H&B Elevators well regarded but bleeding money, Kraus-Anderson decided it was time for a change.

“There were days that we just didn’t know whether or not the doors would be locked,” Eison remembers.

The then-31-year-old project manager wondered what would happen to his customers, company and coworkers. He was searching for purpose; he wanted to make a difference, change his family’s trajectory, and honor the generations that had come before while securing a future for his own children.

When Kraus-Anderson decided to sell the H&B Elevator division, Eison wasn’t on the list of prospects, but he was expected, as a key employee, to educate potential buyers touring the facility.

“They’re going to sell this to somebody,” he recalls thinking. “Then you’re going to work for somebody else who will likely need all of your knowledge.”

Then he thought, “Why not us? Why shouldn’t I take this [opportunity]?”

That opportunity came much sooner than he thought it would, Eison says, as the pull was impossible to resist. “For my kids and my kids’ kids, this could be something legacy-like,” he told himself. “I created this opportunity to do something that you could only think about, dream about or talk about. And then here it is.”

Partnership

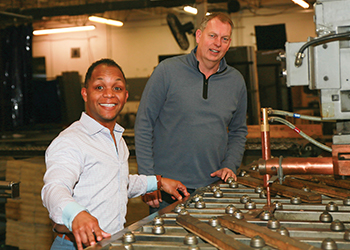

Eison was in his early 30s when he began wrestling with thoughts of purchasing H&B Elevators. He knew there was risk, but he felt good about his experience in the business, while also recognizing he couldn’t go it alone. He needed a strategic partner—someone with a background in finance—and he found it in Fred Poferl, H&B’s current chief financial officer.

Poferl had been with the company since 2003, and he had a knack for numbers and patience. For Poferl, the kind of partnership offered by Eison was similar to one he’d received years earlier by another friend. He’d turned that one down at the time because his family was too young for such a financial risk. Now, he welcomed the chance to make a dream a reality. His temperance balanced Eison’s young, competitive personality, and the pair scrambled to come up with a plan.

Kraus-Anderson rejected Eison and Poferl’s first offer, but the duo refused to give up. It was around that time Eison was encouraged to step away from the purchase.

“You cannot do this,” he was told.

“That was enough for me to keep my fire going to this day,” Eison says. He wasn’t about to settle for “no.”

Poferl and Eison came up with a new pitch to Kraus-Anderson, and negotiations lasted more than a year. Help came from MEDA, which connected the two entrepreneurs with lawyers, advisors and financing. Eventually, Kraus-Anderson saw an offer it couldn’t refuse.

Eison today repays the help he received by serving on the boards of MEDA, Turning Point and the Minneapolis Workforce Development Council.

In hindsight, Eison sees that H&B’s former owners oversaw the transaction with the future—his company’s future—in mind.

“They guided the purchase and the sale in the best possible way that would leave me an opportunity to succeed,” Eison says.

Though the purchase was nearly seven years ago, he sometimes wonders what, if anything, he would do differently today. In any case, Eison is confident that, given a chance, he’d do it all again.

“Sometimes it’s just that knee-jerk reaction,” he says. “Jump. Figure it out. Just make sure you’re not jumping too far, too fast.”

Rebuilding and refining

Poferl and Eison had spent 18 months working alongside their coworkers without letting the big secret slip. When word came from top brass that the pair would be purchasing the company, the news shocked the workforce. But there was no time to celebrate or answer questions. The terms of their arrangement with Kraus-Anderson meant the new owners had to find a new home within a week.

“Good thing I had a truck at the time,” Poferl quips with a smile.

At just over 50,000 square feet, that home—a former clothing warehouse on Washington Avenue in North Minneapolis—had the space but lacked the infrastructure. Metal manufacturing was a different sort of business, and the structure needed power distribution and proper airflow to accommodate H&B. They were working against the clock.

New and existing staff operated across the new and old spaces as contractors installed critical systems. Poferl, meanwhile, traveled the city in his pickup truck, looking for auto shops that could handle custom paint jobs for their products. The new company had inherited a backlog of work, but the quotes given to clients didn’t factor in outsourcing most of the process.

“It wasn’t like we were going to call up our customers and say, ‘We’re going to shut down for a while because we’ve got to make a big move,’” Eison recalls. The team had to adapt.

Some of H&B’s heavier equipment weighed multiple tons, and it was more than a month before everything was in place. Today, after working through that early rocky period, H&B Elevators is sustainable and growing.

Eison is practical in his account, saying success “depends on who’s willing to sacrifice the most for what they want.” Life taught him plenty about sacrifice, and the shuffle and stress of those early months weren’t enough to break him.

“He’s a wonderful leader,” says Bob Kill, president and CEO of Enterprise Minnesota. “They bought a company, moved it into an area that has needed the kinds of jobs and wages they provide, and cleaned up a building that looked like it should have been torn down.”

With their feet back on the ground and margins stabilizing, Eison and Poferl still had a lot of work to do. The story wasn’t over.

They set their eyes on ISO certification and tapped the experience of Enterprise Minnesota to make it happen.

“We always thought it was too expensive, that it was going to get in the way of the business,” Eison says. “But it’s been good for us. We owe them big time because they helped us get here.”

With an ISO certification in hand, H&B’s customers gained a greater respect for the company, seeing the investment in improvement as a commitment to their own businesses as well.

Today, H&B Elevators still faces challenges, but Eison says the stress and obstacles of their first years are behind them.

“That’s just business, right? If you can’t figure that out, well, hang up your cleats and move on,” Eison says, laughing.

But Kill is quick to give credit where credit is due. “When we think of elevators, we think of pushing a button and they go up and down,” he says. “H&B Elevators brings innovation to a product that we don’t think of as being innovative. And they’re known all over.”

Empowering a team

Under Eison and Poferl’s ownership, business is as much about people and relationships as it is about building world-class elevator doors and cabs. Eison says he hasn’t forgotten the lessons his mother taught him. He runs his business like he raises his family, by treating people fairly and doing what’s right. It’s part of the reason H&B actively recruits new employees who haven’t traditionally entered or succeeded in the workforce.

“There’s just so much out there, and we could turn a blind eye to it and pretend it doesn’t exist, or we could be a part of the solution,” Eison says.

He believes that by treating people well, you’ll get the best out of them. And although turnover is still a reality, Eison’s investment in his workforce has helped breed loyalty. Most employees have worked for the company for years, some even for decades. H&B’s region of North Minneapolis faces a shortage of skilled labor, and new hires may never have read a tape measure or worked with metal or elevators, but these disadvantages can be overcome.

“It’s hard to find people, and it’s hard to keep people,” Eison says. “But we pride ourselves on giving folks a chance who wouldn’t otherwise have a chance.”

It’s not only getting employees in the door but training them to work at a high level that’s necessary for a custom business such as H&B Elevators. With a team of 50 employees, Eison partners with veteran staff to shape new team members into future leaders. One of those veterans is H&B’s former cab lead, Wayne Rierson.

Rierson came to H&B in June 1969 straight out of high school. He lived two blocks away and learned everything he needed to know to apply for a job by checking out the company’s parking lot.

“They sure drive nice cars around there,” he thought to himself. “They must make pretty good [money].”

Rierson already knew how to read drafts and was willing to learn whatever he needed to be successful. He says he grew by sharing knowledge, and that’s how he shapes new recruits today.

As Rierson speaks, the sounds of industry fill the H&B Elevators warehouse—air hoses gushing, welders sparking and forklifts hauling heavy loads. He remembers when Eison and Poferl purchased the company in 2013. Of the roughly 30 union employees at the time, he was one of 12 who stayed. The others were intimidated by the loss of union status. Over his 51 years in the shop, he’s watched processes change drastically. Today, H&B works with fiber cell laser cutting systems and automated shears—tools which, combined with better processes, yield faster, more consistent products. But there’s a lot still done by hand.

“There’s still a skill set here,” Rierson says. “A lot of people try it, and some of them, they just don’t catch on.”

Rierson actually retired three years ago, but the company tapped him to come back part-time. And he isn’t the only veteran-turned-mentor guiding the next generation of welders, machinists and engineers.

“We came to help, and we’ve been helping ever since,” he says.

Like Eison, Rierson believes in investing in good people and sound processes. Right now he’s in the process, Rierson says, of “capturing his brain on paper”: writing training manuals that will enable new staff to benefit from his experience.

And maybe the people-centered approach at H&B Elevators makes sense—products inform processes, and elevators are about reaching higher. For Eison, elevating others is more than a metaphor or a mission statement, it’s his life’s story and business model. He weathered a complicated upbringing amidst loss to become an industry innovator.

…

Featured story in the Spring 2020 issue of Enterprise Minnesota magazine.